Most people are aware of the natural beauty which is found in the west of Ireland. Associated with charming wilderness, beautiful coastlines, rugged landscapes, craggy cliffs, rich pastures....... it might surprise some people to learn that Ireland is also home to some of the most stunning beaches in the world, including world class surf!

With 1,800 miles of unspoiled coastline, Ireland’s southern and western shores are the first points of contact for waves originating in the remotest parts of the North Atlantic. These waves get kicked up and are driven on by the relentless Gulf Stream and then, on arrival, are shaped by a pristine reef.

One of the foremost surfing beaches on the west coast is found in Lahinch - a mere 2 miles from Ennistymon.

Lahinch is where 30-foot waves, known as “Aileens”, crash into the famous Cliffs of Moher. Aileen’s Waves have been described by scientists at National University of Ireland Galway as the nearest thing to a “perfect wave”.

But long before the surfers’ arrival, Lahinch’s mile-long beach of golden sand had made the village a popular seaside tourist resort.

In 1887, with the growing popularity of sea bathing and the arrival of the West Clare Railway, tourists began arriving in Lahinch in unprecedented numbers.

In 1892, the sea wall along the promenade was officially opened by the wife of the Irish Viceroy, Lady Aberdeen, and Lahinch become the seaside resort we know today.

My father had told me stories about Gillie, our grandfather, walking from the Sunnyside Cottage in Ennistymon to Lahinch Beach to go swimming. I didn’t realize it then, but his cousins - the Galwey-Foleys - lived in Lahinch at that time. An only child, Gillie must have enjoyed spending time with the four Galwey-Foley boys and he forged friendships with these cousins which lasted their lifetimes.

The matriarch of the family, Ida Burke-Browne Galwey-Foley (1868-1940), was actually Gillie’s first cousin. Her mother, Bessie Reilly Burke-Browne, was his father’s oldest sister. So, Ida’s children were Gillie’s 1st cousins, once removed.

Sixteen year old Ida had married 32 year old Edmund Augustine Galwey-Foley, Esq (1852-1922) on November 4, 1884.

Ida was only 16 when she married Edmund. It is difficult to understand how she could have been married at such a young age to a man almost twice her age. But, our great grandmother was only 16 when she married 33 year old Henry Patrick. Maybe that was one of the bonds shared by both women.

For more information about Ida’s family, check out this post from our blog: https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/05/the-reilly-family-school-bazaars.html

Edmund Galwey-Foley, Esq was a member of two old and established Catholic families who had been associated with County Waterford for generations: the Galweys and the Foleys.

His father, Edmund Foley, Esq of Owbeg (1810-1860) had been the Sub Sheriff of County Waterford for 25 years and its High Constable for 16 years.

These were very difficult positions to hold, especially during the Famine Years. Yet, by all accounts, Edmund had always carried out his duties like a Gentleman.

His obituary describes the esteem in which he was held by his community:

Edmund’s maternal grandfather, John Matthew Galwey, Esq, MP of Abbeyside (1790-1842), was Justice of the Peace and had served Waterford as a Member of Parliament (1832-34).

He was also a successful wine merchant, a ship builder, a landowner, a land agent and a leader in the Catholic Emancipation Movement.

His great uncle, James Galwey, Esq (1800-1888), whom we have previously featured in a post on this blog https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/09/the-story-of-legend.html had been the Inspector-General of Prisons in Ireland, a Director of the Waterford and Limerick Railway, Justice of the Peace and the breeder of the famous Coursing champion, Master McGrath.

Edmund’s older brother, John Matthew Galwey-Foley, Esq, JP (1849-1931) was also a Justice of the Peace and the County Inspector of the Royal Irish Constabulary(RIC).

And, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Esq (1859-1930) - famous author of Sherlock Holmes - was a maternal cousin who had spent several summers visiting relatives in Waterford during Edmund’s lifetime.

In 1870, our Edmund Galwey-Foley began working for the National Bank of Ireland. His first assignment was as an Assistant at the Mitchelstown branch in County Cork.

Four years later, he was promoted to Teller at the Ennis branch.

During the following years, he worked at branches in Gort (1874) Abbeyfeale (1876), Galway (1877) and finally, he was promoted to Accountant at the National Bank on Parliament Street in Ennistymon.

As prominent businessmen in town, our great grandfathers might have fostered a relationship with the 30-something unmarried Gentry Banker…… and perhaps introduced him to Ida whose family was living nearby at Castlepark in Kilmihil........ and the couple was married in 1884.

After her marriage, Ida seems to have developed a warm and close friendship with her cousin's wife, Mary Milward Reilly - our great grandmother. Mary named Ida to be the legal guardian of her only child, Patrick Henry Reilly AKA: Gillie - and the two women shared a love of horseback riding and fox hunting.

((These women are not our relatives......)

For more detailed information about Gillie’s relationship with Ida’s family, check these posts from this blog:

Ida and her new husband lived in Cregg House which was right on Lahinch Beach. Although Cregg House is no longer there, it was situated near the Promenade where these houses sit today.

Ida and Edmund started a family right away and had six children within the next nine years:

Edmund Augustine (1885-1961);

Gladys Mary (1886-1968);

Leopold George Duncan (1888-1984);

Thomas Joseph (1889-1961);

Percy J (1890-1939);

Hilda Evelyn (1894-1967)

The five oldest children were born at Cregg but, in 1891, a violent storm hit Lahinch and Cregg House was one of the houses which were destroyed.

The devastation was so extreme that, in 1891, Lahinch was the subject of debates in the Houses of Parliament.

As a result of the storm, the family must have moved to Ennistymon because Hilda, the youngest child, was born there in the summer of 1894. (Grandpa’s father, Henry Patrick, died a few months later in September.)

As you can see, the Galwey-Foley cousins were all around the same age as Gillie who was born in 1886. Considering the proximity of Lahinch to the Sunnyside Cottage, along with my father’s stories about spending summer days at Lahinch Beach and the fact that Ida and Edmund were his legal guardians, Gillie must have always felt like a member of their family.

At this time in the 19th century, shooting and hunting parties were popular pastimes for the gentry in Ireland.

In terms of access and the expenses involved in this “sport”, shooting has always been, and still is, an exclusive domain enjoyed by the wealthy and the “well connected” - simply by virtue of the fact that one either had to be a landowner, or share a similar social status with a landowner, in order to be invited to Shooting Parties.

In previous posts, we have mentioned the familiarity some members of our family had had with shooting and hunting.

As its Land Agents, both our great grandfather, Patrick Edward Reilly, and his son, Henry Patrick Reilly, were very much involved with Ennistymon House which was well known for hosting lavish weekend shooting parties during the 19th century.

We know that Henry Patrick owned a series of hunting dogs throughout his life. https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/05/its-dogs-life.html

We think Gillie earned his nickname due to his ability to stalk game. https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/05/what-in-name.html

We related a story that Edmund’s son, Leo, told about hunting for rabbits in Ennistymon. https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/08/from-ennistymon-to-cariboo-wagon-trail_11.html

Here is another story about Leo and his familiarity with hunting. It was found in the Archives of Blackrock College:

We published a post about Edmund’s great uncle, James Galwey, who had bred the famous coursing champion greyhound called Master McGrath. https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/09/the-story-of-legend.html

And, there were the stories that my father had told me about Grandpa taking him hunting for pheasants on Calhoun Avenue in the Bronx. https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/05/what-in-name.html

So, it comes as no great surprise that sporting dogs were important in the lives of Edmund Galwey-Foley and his sons ...... and Gillie.

According to Father Edmund O’Keefe, SJ (Hilda Galwey-Foley’s son):

‘the entire Galwey-Foley family loved the sporting life of the Gentry.

Anything to do with animals - hunting, shooting, riding, dogs - was their passion.

Once sport were involved, it mattered not whether the location was Kildysart, Leopardstown, Cheltenham or New Jersey -

the Foleys were ready!’

In 1865, dog licenses were introduced into Irish law. A license cost 2 shillings per dog plus an extra 6 pence for administration costs.

Just as I did for Henry Patrick, a search of the Register of Dog Licenses produced a list of the dogs owned by the Galwey-Foley family from 1873 until 1912 (with a few gaps).

Most of the breeds he preferred were considered “gun dogs” which were bred mostly for hunting birds and small game.

These include all of Edmund’s breeds - setters, terriers, pointers, and water dogs.

Between these dates (1872-1912), he registered 11 Irish Terriers, 15 Irish Red Setters, 8 English Pointers, 8 Waterdogs, 7 Fox Terriers, 1 Pug.

The Irish Terrier was one of Edmund’s favorite breeds. Determined hunting dogs, Irish Terriers will stop at nothing to get to their prey.

VERY fast and tenacious, the Irish Terrier is brilliant for hunting around water and are good swimmers. Their speed and agility make them excellent bird dogs.

The list of Edmund’s dogs included 7 Fox Terriers which are not necessarily gun dogs but were bred to run with the hounds and horses. After chasing the prey, Fox Terriers were known to go to ground and pursue the quarry into its den.

Throughout her life, Ida was well known as an accomplished equestrienne. Maybe these fox terriers belonged to her.

In 1922, her cousin, William Patrick Gavin of Kildysart House, published his reminiscences of equestrian life in the hunting fields of county Clare.

Titled: True Sporting Verse, in the third of his thirteen verses in praise of Ida ........"a lovely young woman", Gavin writes:

"No matter what kind of horse she got on,

Trained or untrained ''twas the same,

For a minute she got up and sat on their backs,

They became gentle and tame."

There were 15 Red Irish Setters in Edmund’s kennel.

The Red Irish Setter is a bird dog with a high prey drive, dedicated work ethic, and great stamina.

A dependable gun dog, highly skilled in sniffing out and pointing to the hiding spots of grouse and game birds, Red Irish Setters were granted favor by 19th Century landed gentry who considered them their working dog of choice.

The breed was originally used to “set” game - crouching low near the birds so that the hunters could walk up and throw a net over bird and dog. When firearms were introduced, the Irish adapted into a gun dog that pointed, flushed and hunted in an upright stance.

The Red Irish setter takes a backseat to none as a bird-finder deluxe and rugged all-purpose hunter.

Edmund probably hunted pheasants with his Setters.

Edmund had registered 8 Waterdogs between 1886 and 1900. Waterdogs are gun dogs who are bred to flush and retrieve game from water. A strong swimming desire is a characteristic of these dogs. Some of the oldest dog breeds are water dogs.

The Irish Waterdog is instantly recognizable by its crisply curled coat and tapering “rat tail.” Among the champion swimmers of dogdom, the alert and inquisitive IWS is hardworking and brave in the field, and playfully affectionate at home.

Finally, there were 8 English Pointers registered by Edmund between 1887 and 1903.

Speedy and durable enough to last all day in the field, Pointers are also known to “stand steady to wing and shot,” meaning it will hold its pointing position for over an hour, even when the birds fly and the guns blast.

The dog’s pointing directs the hunter toward the hares or birds in question. Their ability to hold their position also meant they wouldn’t startle any prey before the hunter could cast a net over them.

In 1901, the Galwey-Foleys registered a fawn colored Pug - which, probably, was a companion dog for Ida and her daughters.

Pugs originated in China where they were bred to be companions to the royal families who loved, adored, and spoiled them rotten. The royals couldn’t keep them to themselves for too long before the Pug Bug spread across Asia and then the rest of the world.

Pugs soon became the preferred dog of choice for Queen Victoria and, under her reign, the breed flourished throughout her Empire.

Queen Victoria’s visit to Ireland in April 1901 caused much excitement throughout the country. The people went crazy ....... parades, celebrations, newspaper editorials........ the entire country caught Royal Fever.

The Galwey-Foleys adopted their Pug in 1901 - perhaps they caught the fever, too.

So, as you can see, the Galwey-Foleys - and Gillie - were always surrounded by skilled gun dogs and hunting was an important part of their life.

From what I have already learned, I don’t think Gillie enjoyed a good relationship with his own father but he must have enjoyed his association with the Galwey-Foley family and was probably always included in their shooting parties.

This is an amusing incident that I found in the 1885 Petty Sessions Records. It makes me wonder if Edmund might have been a curmudgeon.

Evidently, on October 24, 1883, Michael Leyden

“....... did furiously drive a horse and cart on the public road so as to endanger the life of complainant .....”

Edmund was the complainant and sued Leyden in the Petty Sessions Court.

The matter did not come to court for two years, in November 1885........ guess Edmund was still upset.....

Michael Leyden was found guilty but his sentence was delayed until the next court date..... which was not recorded.

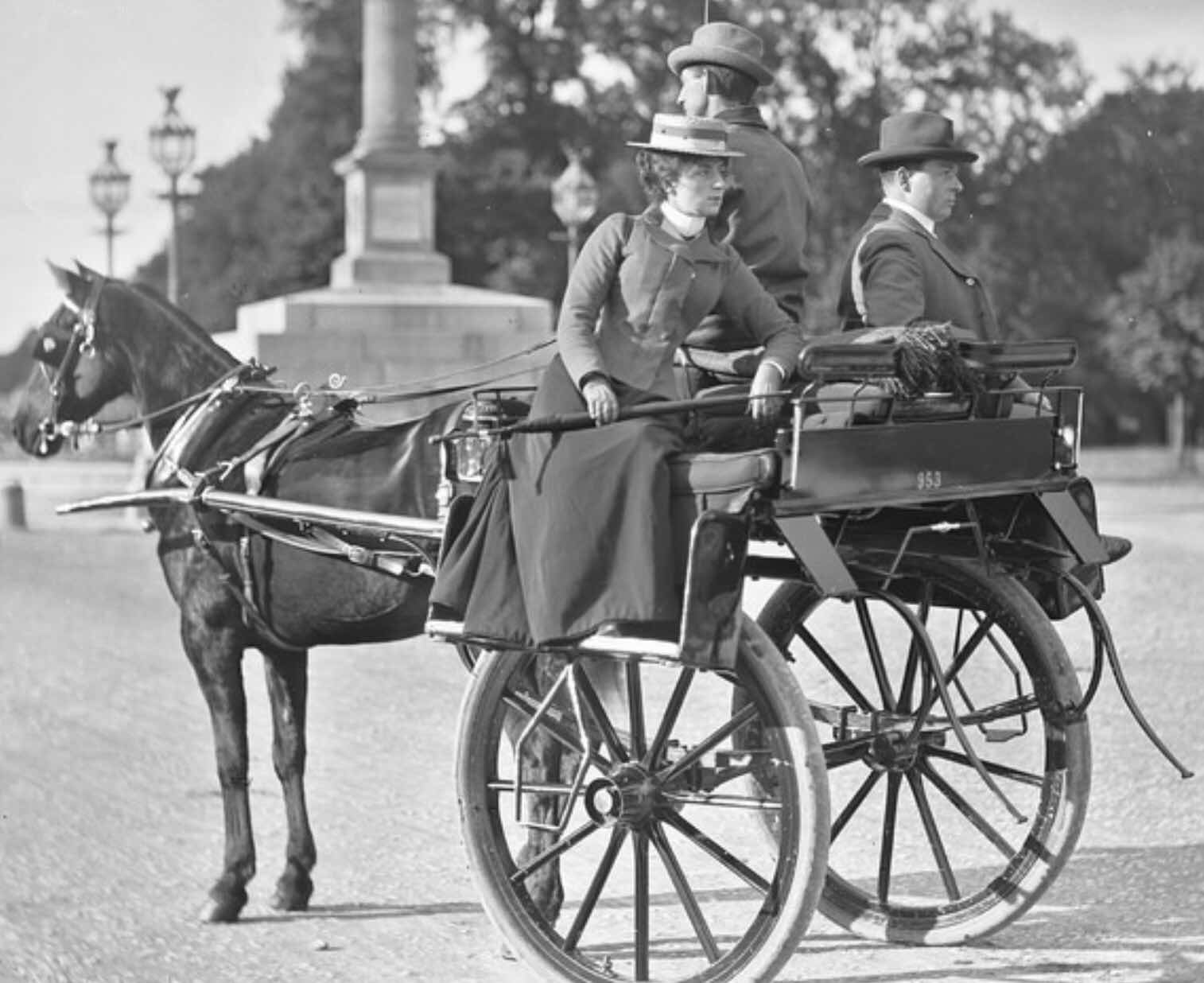

Edmund had spent 13 years working as the accountant of the National Bank in Ennistymon. To get to the Bank on Parliament Street from Cregg House in Lahinch, he would have had to drive his jaunting car right up Lahinch Road into Ennistymon - right past the Sunnyside Cottage.

Up until the early decades of the 20th century, the jaunting car was the typical mode of transport preferred by the Gentry in Ireland.

Its body was mounted on springs, with only two wheels underneath.

Two long wooden seats were placed lengthways so the passengers sat facing out, sideways while travelling. In the front was an elevated driver's seat.

At that time, jaunting cars, which are unique to Ireland, were ubiquitous all over the country. On average, it would take three hours to cross 15 miles in a jaunting car.

If you remember, Ida Burke-Browne Galwey-Foley had six sisters.

In 1892, four of those sisters - Frances, Adelaide, Agnes and Louisa - were all still living in their grandmother’s ancestral home in Tulla - Grove Ville.

At the time, they were having trouble with some of the tenants on the property.

On December 31, 1892, the ladies and one of their servants were in the kitchen and noticed two strangers approaching the home. One of the men opened the door and fired four shots into the kitchen and fled. The shots barely missed one of the women.

Police were called and two bullets were found embedded into the wall.

The news hit newspapers throughout the United Kingdom and even in the New York Times!

The intruders were never found but were identified as “Moonlighters”........ and the ladies were described as “plucky”!

This is the sort of violence that was associated with the Land Wars which was occurring quite often in County Clare during the last half of the 19th century.

Although the Land League was urging peaceful means of protest, many of the dispossessed tenants took the law into their own hands and joined a secret agrarian society, headed by the mysterious Captain Moonlight, to attack landlords' property, particularly their livestock.

These attacks, known locally as "moonlighting", in turn prompted reprisals, creating a spiral of violence.

In the 1890s, the West of Ireland was frequently disrupted by violent Land War "outrages" which pitted landlord against tenant.

The year 1894 opened the door to some drastic changes in the lives of Gillie and the Galwey-Foley family. The next ten years of Gillie’s life were filled with stress and loss.

1894 was the year Gillie’s father, Henry Patrick, died in the Ennis Lunatic Asylum.

Not long after, the Galwey-Foleys left County Clare. Edmund had been promoted to Manager of the National Bank in Carrickmacross, County Monaghan - 175 miles from Ennistymon.

Shortly later, Gillie and his mother left the country life in Ennistymon to live in the capital city, Dublin.

And, within another four years, in 1904, his mother died, too.......

Although he was now an orphan, Gillie was reunited with his cousins because Ida and Edmund were his legal guardians..... so he moved to Carrickmacross to live with them. He was about 17 years old.

At the time, it was customary for the National Bank to provide housing for its managers and families.

These Bank Houses were usually very fashionable and big enough to accomodate large Irish families along with the requisite 2 or 3 live-in servants.

In Carrickmacross, the Galwey-Foleys lived above the Bank at 26 and later at 31 Main Street.

As we might imagine, the Bank House on Carrickmacross’ Main Street must have been a very large home to accommodate a family with seven growing children and teenagers.

Having been in Carrickmacross since about 1896, the family had pretty much settled into their new surroundings by the time Gillie joined them in 1904. .

As wife of the manager of the Bank of Ireland, Ida kept herself busy spreading goodwill in her new community - as was professionally expected of her.

In 1907, she participated in the annual Carrickmacross Agricultural Show and even won a prize for her flowers.

But, by 1904, two of the four sons were soon to leave home.

The eldest son in the family was Edmund Augustine (1885-1961). He started working for the National Bank in 1905 as a clerk at the Carrick-on-Suir branch in Tipperary.

And living in Drohan’s Rooming House on Castle Street:

The next oldest son, Leo (1886-1984) emigrated to Canada in 1906.

Read more about Leo’s life of adventure in this post - https://ennistymon.blogspot.com/2017/09/backup-backup-backup-backup-backup-from.html

But, Thomas Joseph - our Uncle Tom Foley (1889-1961) - was still at home when Gillie arrived - maybe that was why the two of them remained close lifelong friends. Uncle Tom would emigrate in 1911, three years after Gillie.

The two sisters - Gladys Mary (1886-1968) and Hilda Evelyn (1894-1967) - were still home. They would move to Dublin with their parents when their father retired in 1914.

The last and youngest son at home was Percy J (1890-1939).

Percy was only six years old when the family left County Clare and, in 1904, he was going to Patrician High School in Carrickmacross.

In 1902, the 'Religious Congregation of the Brothers of St. Patrick’ - the Patrician Brothers - had been invited to establish a school for boys in Carrickmacross.

Initially, classes were held in two rooms in the rectory - but there were only eight students at the time!

Shortly after, the school was relocated next to St Joseph’s Church on O'Neill Street.

Patrician High School moved to a modern home in 1971 but Percy attended class in this small building.

From the early 1870s, there had been a growing demand in Ireland for a competitive examinations system which would allow Catholics, in particular, to earn admittance into the secondary school system.

Graduation from a secondary school opened the door to employment in the newly created jobs in the civil service and for careers in the professions.

In response to this pressure, the Irish Intermediate Education Bill was introduced to Parliament in 1878.

It provided an Examining Board with an annual sum of £32,500 which would cover money prizes for pupils and results awards for schools.

Students with the highest marks could gain valuable exhibitions worth up to £50.

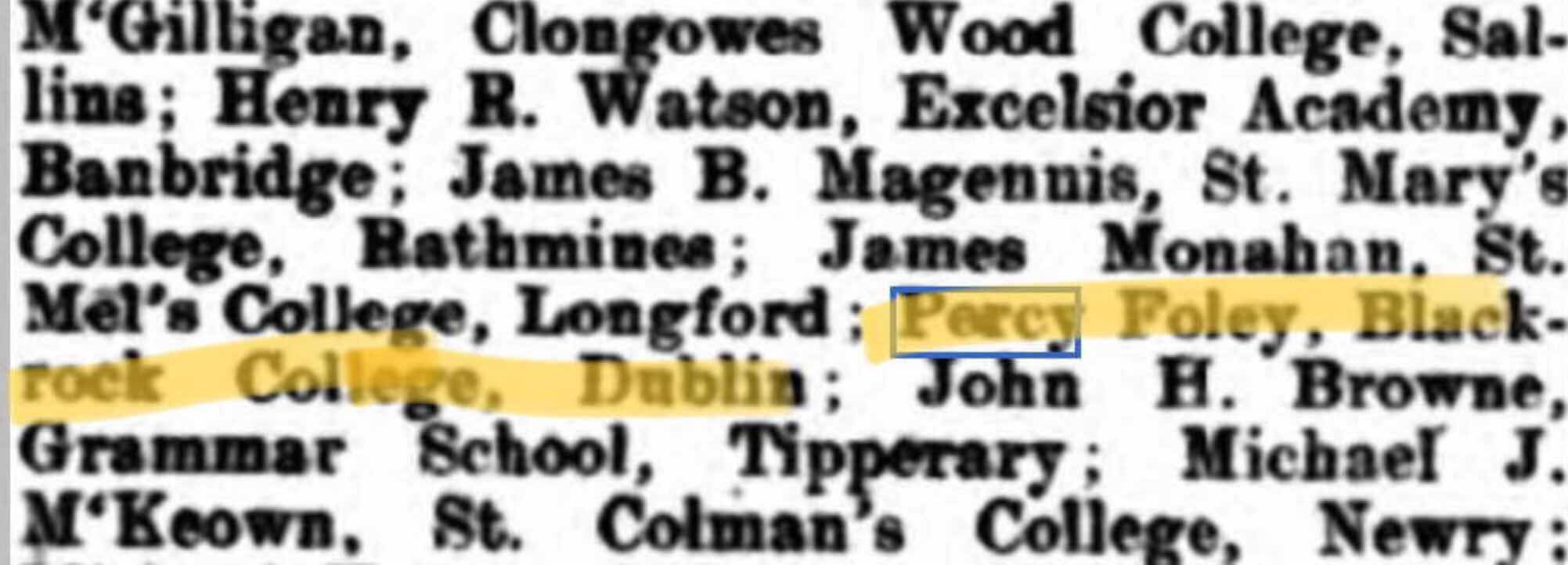

It is obvious that Percy was a good student. He received awards for excellence every year.

In September 1905, his first semester at Patrician, he won an Award of £3 in his Modern Literacy Course.

His second year at Patrician, Percy again earned an Award in Modern Literacy but this time, he won £10!

1907 was Percy’s last year at Patrician High School and his performance did not disappoint.

In March, there was a nationwide French Translation Contest in which he earned a mention.

In addition, that September, he was also awarded another £2 for his performance in Modern Literacy.

After graduating from Patrician, Percy continued his studies at one of the most prestigious and exclusive schools in Ireland: Blackrock College in Dublin.

A great many Blackrock graduates entered Ireland’s Civil Service because Blackrock, in addition to its university program, had a very successful civic service training department where students were examined and earned degrees which were recognized and conferred by the Royal University of Ireland.

By the end of the 19th century, the education of wealthy and influential Catholics was split between several high-profile domestic boarding schools such as Clongowes, Castleknock, and Blackrock.

Graduates of these elite schools have long enjoyed a disproportionate penetration into the upper echelons of Irish public life.

Set in 56 acres of rolling parkland on the broad sweep of Dublin Bay and just four miles from the center of Dublin, Blackrock College was founded by the Congregation of the Holy Ghost - French missionaries - in 1860.

Blackrock - also known as the French College - had a dual aim: to educate young Irish boys and to be a training center for careers in Civil Service.

Its highly successful Civil Service training department flourished for forty years.

Percy was enrolled at Blackrock College as a boarding student from 1907 until 1908.

In September 1908, he won two awards: a medal for Mathematics:

He also earned £3 for his performance in Modern Literacy:

Although the Irish Civil Service Commission was said to be

“..... practically a reproduction of the British system....”

its chief aim was to serve Ireland as

“....the first line of defense against nepotism, jobbery and corruption....”

that had always characterized public service appointments under British rule.

So, in developing its own Civil Service, the Irish Commission did everything possible to rid the service of the patronage and favoritism which were rampant in Britain.

Young men (no women need apply) hoping for a career in civil service or in the Royal Irish Constabulary were recruited by open but very competitive examinations.

To improve one’s chances of success, candidates frequently enrolled in “grinder schools” which offered intense tutelage in passing these examinations.

After leaving Blackrock, Percy enrolled in Connell’s Institute which was located in Derry.

In November 1910, Percy took the examination for the Customs and Excise position. Connell’s Institute took advantage of this opportunity to promote their business. Percy scored 87th Place in the United Kingdom.

He didn’t waste any time - a month later, he took the exam for Second Division Clerk and scored 77th Place in the UK.

A month later, it was announced that Percy had gotten the job!

((Connell’s Institute continued to brag about Percy’s success in their newspaper advertising.))

In the Irish public service system, clerks were divided into two categories.

First Division Clerks were members of the administrative grade and were entrusted with duties demanding a “considerable degree of initiative and judgement.”

Second Division Clerks - the executive class - performed tasks of a more routine nature. They numbered 500 clerks working in 15 departments and were the backbone of the Civil Service in Ireland.

Clerks usually entered at the Second Division Level and would then compete for positions in the First Division. They would prepare themselves for this competition by taking more classes and by attending lectures.

Percy received his first assignment in Civil Service in March 1911.

Until 1919, he served in the Office of National Education which is in control of policy, funding and the direction of education in the country.

Meanwhile, in 1914, Edmund Augustine Galwey-Foley retired from the National Bank of Ireland.

He, Ida and their two daughters, Gladys Mary and Hilda Evelyn left the Bank House in Carrickmacross and moved to the Rathgar neighborhood of Dublin at 48 Grosvenor Road.

Rathgar was then and remains now one of the most desirable neighborhoods in Dublin. Its red-brick Georgian and Victorian terraces, results of the architectural experimentation of the 19th century, are home to some of the most impressive houses, churches and schools in Ireland. Rathgar’s residents have also proved to be some of the most influential in Irish political, social and cultural life.

Grosvenor Road in Rathgar is a wide, quiet road lined with many different styles of Victorian houses, mostly in pairs or short terraces.

What the period redbricks all have in common is that they are very large imposing houses.

Built in 1860, 48 Grosvenor Road is a two-story terrace house with three bedrooms and three baths and about 2,400 sq ft.

From the street, these homes look quite ordinary making it difficult to appreciate the elegance and spaciousness found inside.

To get a better idea of the interior of 48 Grosvenor Road, here is a description of 32 Grosvenor Road which recently sold for €1,560,00 -

Throughout the property, there are delightful original features that have been carefully restored,

such as original cornicing and centre roses, marble mantelpieces and cast-iron fireplaces.

As you walk through this charming home, one is struck by the wealth of natural light.

Throughout the home, every room offers generous and well-proportioned living space,

very much conducive to formal entertaining and relaxed living.

Upon entering the property, one is greeted by a grand entrance hall with its high ceilings and ornate ceiling plasterwork.

The original fanlight allows for natural light to stream into the hallway also.

The hall opens into formal interconnecting reception rooms.

Both reception rooms offer high ceilings with cornices and restored centre roses.

Rising to the first floor via a beautiful staircase one is greeted by three large double bedrooms, one ensuite

and a family bathroom on the return and a further wc on the half-landing to the garden level.

At garden level, there is a large family room with an open fireplace and double doors leading to the rear garden.

To the rear is an ease of maintenance and private south west facing garden, ideal for al fresco dining and entertaining.

So, it was to 48 Grosvenor Road in Dublin where Edmund and Ida retired with their two daughters, Gladys and Hilda in about 1914.

Gladys was 28 when she was hired as a Clerk at the National Bank of Ireland on July 15, 1915 and she served the Bank almost entirely at the Rathmines branch until retiring in 1935. She had just a nine minute walk to commute to work everyday.

According to our cousin, Father Edmund O’Keefe, SJ, Gladys’ sister (his mother, Hilda) also worked at the same Bank in 1917. However, the archivist of the National Bank could not locate any records for her.

In 1916, oldest son, Edmund, was promoted to Assistant at the Bank branch located on Great Britain Street (now O’Connell Street) in Dublin.

And, he moved into 48 Grosvenor Road with his parents and sisters.

At the same time, Percy was working at the National Education Office in Dublin. Since, at least 1908, he had been living in a boarding house at 18 Hume Street. We know this because, according to his travel papers, our grandfather spent his last night on Irish soil with him at that address. Percy was still living there when the Census was taken in 1911.

Hume Street is a historic Georgian street near St Stephen’s Green in the heart of Dublin. Just a short walk to both the Government Buildings and the National Education Office, it was very conveniently situated for Percy.

Most of the homes in these neighborhoods exemplify the iconic structures for which Dublin is famous. For the most part, the exteriors of these Georgian houses appear relatively simple with little ornamentation. Typically, the front facade consists of fairly plain brickwork which is only broken up by several long windows.

However, if the 18th century squares and streets of Dublin are famous for any one decorative architectural feature, it is the colorful front doors of these structures with their amazing array of unique fanlights.

And Hume Street offers a prime example of these beauties. Here is a close up of the fanlight at 18 Hume Street:

In 1916, everyday life in Dublin exploded.

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, a group of Irish nationalists proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic and, along with some 1,600 followers, staged a rebellion against the British government’s presence in Ireland.

((The grandfather of Alison Schweppe McCormick - our cousin, Tommy’s wife - was one of the leaders of the Rising.))

What happened next would cause carnage on the streets of Dublin, trigger a brutal British response, transform many Irish people’s attitudes toward independence and set in motion a series of events that would lead to the partition of Ireland.

For a week, the rebels seized and controlled prominent buildings and clashed with British troops on the streets of Dublin.

Rebel strongholds were continuously pounded by British artillery, heavy mortars and even by a gun boat on the River Liffey. A square mile of central Dublin was reduced to smoking ruins. Still, the rebels fought on against almighty odds, until one by one, their garrisons fell and they were forced to accept the only terms on the table: unconditional surrender.

Although the insurrection had been suppressed and had ended in bloody failure, its legacy would transform Ireland forever.

In the aftermath, Dublin city center was almost completely destroyed. Streets had been barricaded and houses, shops, and public houses had been commandeered to create fortress-like protection against the advancing British army.

Five hundred people were killed during the fighting. Three hundred of the dead were civilians.

The bodies of those killed in the Rising littered the streets of the city and an epidemic was feared. Glasnevin cemetery recorded burying 197 bodies of those killed in the rebellion - all of these casualties were from gunshot wounds.

Initially, there was little support from the Irish people for the Easter Rising. The rebels were booed and stoned by Dubliners as they were led off to imprisonment by British soldiers.

But in May, the British Crown exhibited unpardonable and tactless brutality when they executed - by firing squad - 15 leaders of the uprising.

More than 3,000 people who were suspected of supporting the uprising, either directly or indirectly, were arrested, and some 1,800 of them were sent to England and imprisoned there, without trial.

These rushed executions, mass arrests and martial law (which remained in effect through the fall of 1916), fueled public resentment toward the British and were among the factors that shifted public opinion and helped build support for the rebels and the movement for Irish independence.

Being Bankers and landowners, most likely, our family did not support the rebellion. Their life was a good one under British Rule and the status quo suited them.

Although the Galwey-Foley family was living in Dublin during the insurrection, most of the bloody fighting took place south of St Stephen’s Green (about 2 miles from Grosvenor Road) and on the other side of the Liffey River.

I’m sure their life was interrupted but I have no idea what their response could have been. I wonder how our grandparents in America felt about what was happening in their homeland.

While Edmund, Gladys, Hilda, Percy and their parents were living in Dublin, their sons, Leo and Tom, had embarked on a more adventurous life in the New World.

In June 1917, Leo was fighting in France while serving with Canada’s 52 Field Artillery.

His brother, Thomas (Uncle Tom Foley) was living in Salt Lake City where he had enlisted in the US Army, serving until 1919.

In January 1920, Percy was promoted to Junior Executive Clerk (a position he held for nine years).

Sadly, on March 13, 1922, Edmund Galwey-Foley died in Dublin. He was 70 years old and was buried at Deans Grange Cemetery in Dublin. Percy and Edmund were still living in Dublin, at the time but I do not know if Tom or Leo returned to Ireland to be with their mother during the funeral. I could find no travel records for this period.

Ida continued to stay in her Grosvenor home with her daughters after Edmund’s death. She was only 53 years old when she was widowed.

In her younger days, Ida had been known as an excellent equestrienne. She and our great grandmother were very fond of fox hunting - side saddle, of course.

Her cousin, William Patrick Gavin, had been the Master of the Kildysart Harriers and in 1922, he published his memoir of equestrian life in the hunting fields of county Clare.

Titled: True Sporting Verse, in the third of his thirteen verses in praise of Ida ........"a lovely young woman", Gavin writes:

"No matter what kind of horse she got on,

Trained or untrained ‘twas the same,

For a minute she got up and sat on their backs,

They became gentle and tame."

Of Ida’s six children, only one married and had children. On July 26, 1926, Hilda Evelyn Galwey-Foley married Thomas Joseph O’Keefe in Dublin.

Thomas was, of course, a banker!

The couple had four children - one daughter and three sons: Edmund (1927-2011), Fergus (1933-), Mary (1935-) and Niall (1936-2013).

Mary and Niall married and had children.

Edmund and Fergus entered the Society of Jesus.......

Father Fergus is serving in Dublin at the Gardiner Street Parish, St Francis Xavier.

Father Edmund was my compadre and mentor in the research of our family’s history. He had done most of the early legwork - and I do mean “legwork” - before the age of computers! His encouragement and counsel were indispensable to me and I value his patience with this novice-genealogist.

Together, we would commiserate about our incredulity when confronted with family members whose eyes would glaze over whenever we yearned to share our discoveries!

Rest In Peace, Father Edmund.

After a brief time in County Down, the O’Keefes raised their family in Dublin.

Thomas died in 1964 and Hilda passed away in 1967.

Percy left Dublin in April 1929 to be the Passport Control Officer in Boston. Among his duties, Percy was responsible for checking the eligibility of all individuals wanting to enter Ireland.

A few months later, in October, he was transferred to the Department of Foreign Affairs and appointed Vice Consul in Boston.

When the consulate in Boston was established in April 1930, Percy became its first Consul.

At this time, he was living at 288 Chestnut Hill Avenue in the Brighton area of Boston.

Percy Galwey-Foley was quite a Renaissance Man. He was known to be an authority on economics, social philosophy and diplomatic technique. He was fluent in French and he was considered a prominent lecturer on Irish problems.

He returned to Dublin twice - in 1932 and 1935.

In 1938, his office in Boston was at 84 State Street, Room 718 -

He was living in an area of Boston known as Beacon Hill at 113 Revere Street -

Lining the steep hills of Beacon Hill are Federal-style and Victorian brick row houses which are lit by antique lanterns making it one of Boston’s most picturesque areas.

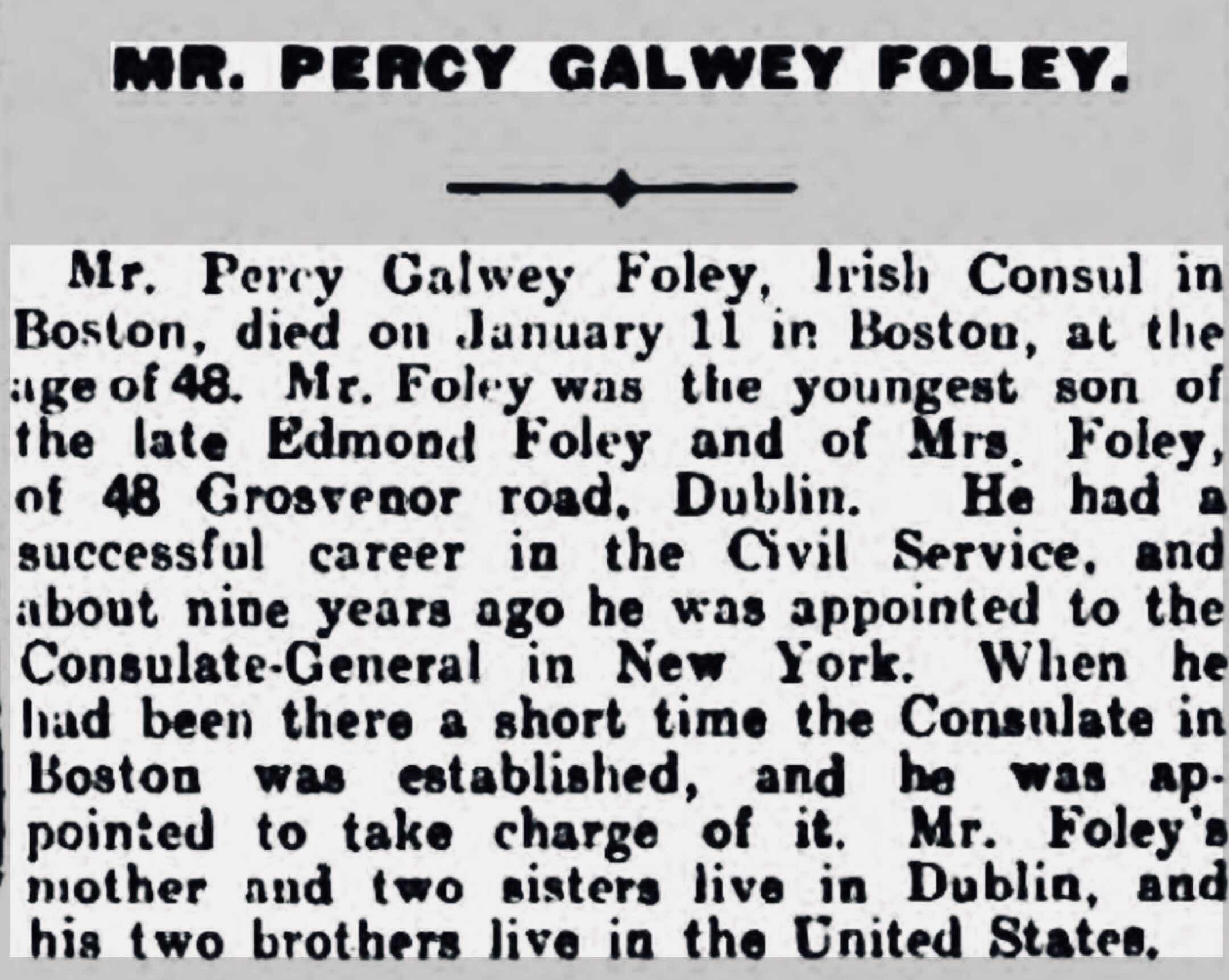

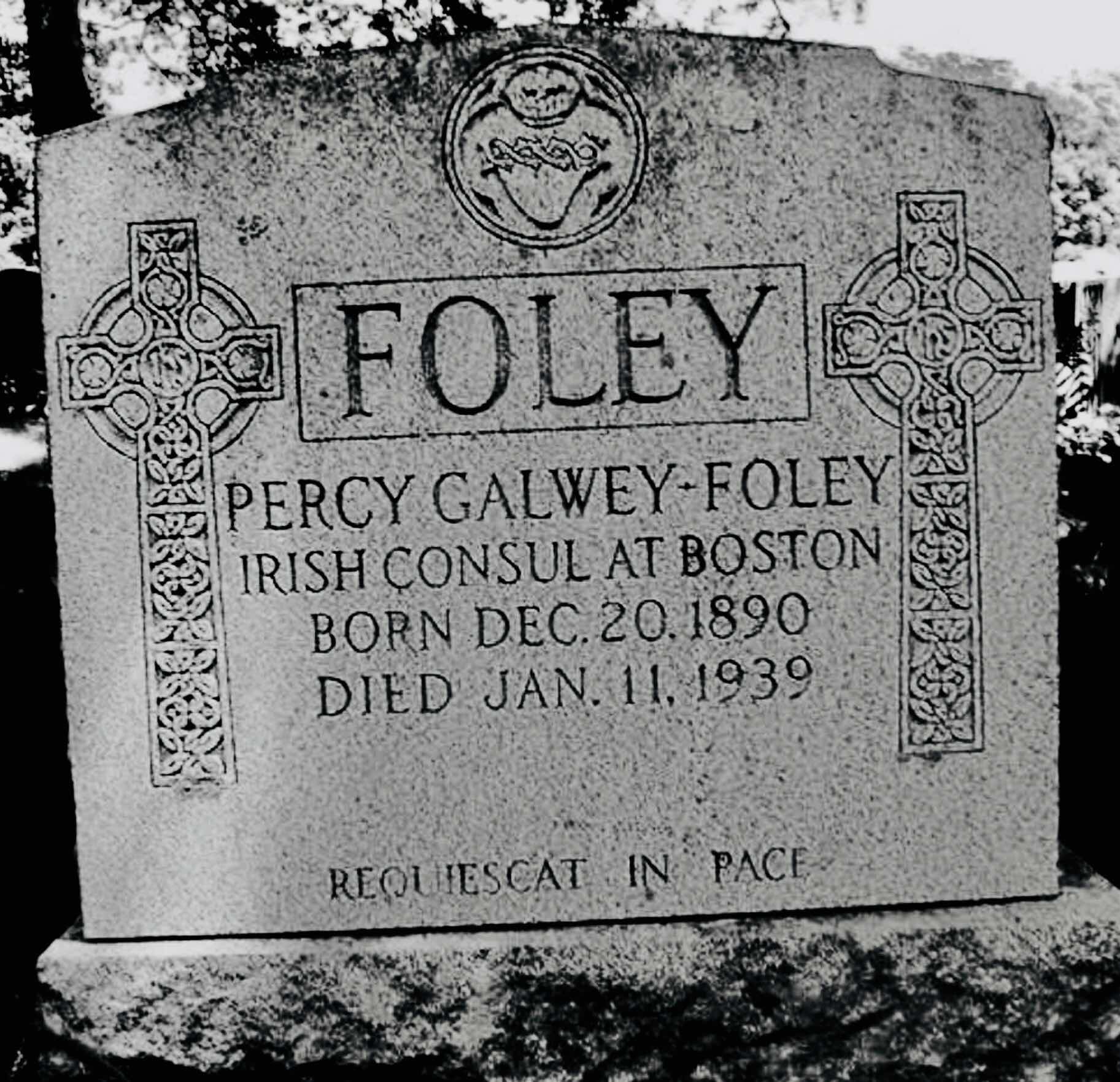

Unfortunately, in October 1939, Percy was diagnosed with leukemia and he passed away on January 11, 1939. He was only 48 years old.

Newspapers all over the world carried his obituary.

The Irish Government issued this statement:

Funeral announcements appeared in Boston and in every major city -

Percy’s funeral was attended by several hundred mourners. A solemn requiem Mass was celebrated at St Joseph’s Church on Chambers Street.

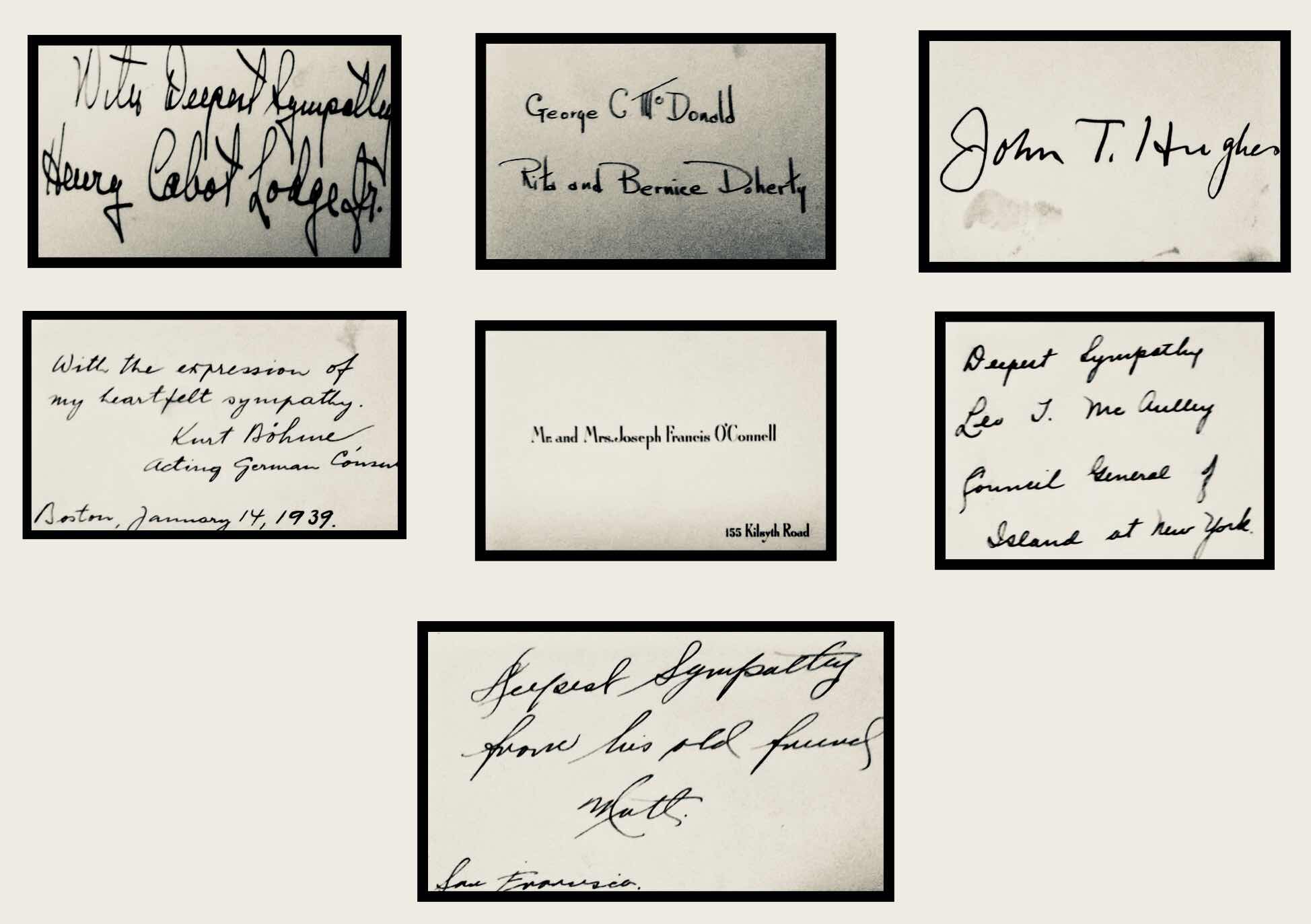

St Joseph’s Church must have been filled with Floral Sympathy Bouquets. Below are some of the sympathy cards received by the family.

Percy was laid to rest at St Joseph’s Cemetery in East Roxbury -

I am not sure if any family members were able to come to Boston for Percy’s funeral.

At the time, Leo was mining for gold in British Columbia.

Tom was working for the Pennsylvania Power and Light Company in Hazleton. Perhaps he attended the funeral. I don’t know if our grandparents did.

In his Will, Percy designated $1,000 for his funeral and $2,500 to his 3 brothers.

Referring to his sisters and mother in Ireland:

“I leave only my love and affection in the firm belief they have otherwise been amply provided for.”

On September 27, 1940, Ida Anna Burke-Browne Galwey-Foley passed away. She was buried with Edmund in Deans Grange Cemetery.

Some time after their mother’s death, Edmund and Gladys moved from 48 Grosvenor Road in Rathgar to 3 Clareville Road in Harold’s Cross - just a 12 minute walk away.

The attached unit at 2 Clareville Road is on the market and here is its description:

With high ceilings and ornate coving,

centrepieces and picture rails reflective of its charming era,

this spacious family home offers a spacious reception hall

Which leads to interconnecting drawing and dining rooms,

both with open fireplaces.

I don’t know for sure but this move seems like it might have been a matter of downsizing for Edmund and Gladys since this area is not as posh as Grosvenor Road. At any rate, with five bedrooms and two baths, I am sure they were very comfortable in Harold’s Cross.

On March 25, 1961, Percy’s oldest brother, Edmund Augustine Galwey-Foley passed away. He was buried in Deans Grange Cemetery with his parents.

Uncle Tom Foley died of cancer that same year on November 14, 1961 in Hazleton, Pennsylvania.

I spent much of the summer of 1961 with my Kelly cousins in Elberon, New Jersey and I remember that Uncle Tom was living there with the family. He had no other family, really. He was Aunt Anna’s godfather and she had welcomed him into her home to take care of him before he died.

Thomas Joseph Galwey-Foley was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Drums, Pennsylvania on January 15, 1962.

Hilda Evelyn Galwey-Foley O’Keefe was the next sibling to pass on - she died in 1967, three years after her husband.

Gladys Mary Galwey-Foley died on December 14, 1968. She, too, is buried with her family in the Lower, North section of Deans Grange Cemetery in Dublin.

Leopold George Duncan Galwey-Foley was 95 years old when he died at Lake Williams, British Columbia in 1984. He is buried about 75 miles from the claim he had staked and mined alongside the Cariboo Wagon Trail at Likely, the marker on Tim's grave reads:

+ Galwey Foley, Leo (Tim) 1887-1984

Rest in Peace.

For more information about his life, please click here:

And

I hope you have enjoyed reading about Percy Galwey-Foley and his family. The Galwey-Foley’s were a very important and influential part of our grandfather’s life.

I also want to thank our Aunt Anna Margaret Reilly Kelly and Ellen Kelly Spirito for making copies of Percy’s obituaries and condolences cards. Their generosity is greatly appreciated - those details make all the difference!

EPILOGUE

History gives a nation its bearing on what it is and how its people are affected by what has happened in the past.

Its kings and queens, its wars - with victories and defeats - these all mold a nation’s culture into the way it views itself in the present.

In the same way, a family history presents how a family has survived and come to terms with the great social and cultural experiences of the ages.

We hope these stories will give each member of our family a foundation and, in some small way, explain how we came to be what we are today.

Hopefully, through these vignettes, our future generations will gain a knowledge of the energy and dynamism, the loves and hates, the errors and mistakes, the victories and failures, the struggles and successes that make us what we are.

Our family history presents a fascinating read - and, hopefully, some lessons to be learned in the process.