That post concluded with the deaths of Edwin and his wife. When that post was first published, the fate of their only child, Gladys Muriel Milward, was unknown.

After her husband’s death in 1907, Gladys’ mother was committed to a Lunatic Asylum in Dorset. For the remaining 30 years of her life, Enid Plumridge Milward never left that Asylum. She died there in 1942.

Gladys’ trail went cold in 1908 when she was 15 years old. The last documentation found for her was her name on the Passenger List of a ship which had sailed from Southampton to Colombo, Ceylon on November 20, 1908.

That was it. Curiously, there was another familiar name on that Passenger List: Gladys’ maternal uncle - King Hermann Plumridge (his actual name) - was also sailing to Ceylon on the same ship. In 1908, King Hermann was a Tea Planter in Ceylon.

Taking a leap:

Since he was Enid’s brother, King Hermann undoubtedly was aware of Gladys’ family situation. Perhaps he had invited his young 15 year old niece to come to Ceylon with him.

But, that trip to Ceylon is where Gladys’ trail had ended....... We could uncover no additional information about Gladys.

That is - until a week or so ago when, on another matter, I made contact with a fellow family historian who lives in Ireland.

After reading about Edwin on this blog, she did her own “digging” and she found Gladys and her family!

So, it is with great pleasure that we present the story of Gladys Muriel Milward Brymer and her family!

To catch yourself up to speed, before continuing, please take a moment to read the post about Edwin Oswald Milward -

After graduating from Edinburgh University School of Medicine in 1879, Edwin Oswald Milward enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and was stationed in Southampton where he met his future wife, Enid Susan Plumridge.

They were married at Christ Church in Freemantle on September 26, 1889 and lived with Enid’s widowed mother, Lady Georgiana Skinner Plumridge, at 141 Millbrook Street until Edwin had received his orders to report to duty in India in 1892.

Since their daughter, Gladys Muriel, was baptized at St George’s Church in Agra on December 22, 1892, we can safely assume that Enid accompanied her husband to India.

During their 6 or 7 years (1892-1899) in India, the Milward family lived in a “cantonment” (military garrison) in the Bengal.

Recollections of British domestic life during the Raj present a picture of an existence that was, in some ways, luxurious but, in other ways, sometimes spartan and filled with difficulties.

British military officers and their families generally occupied commodious bungalows and they commonly employed numerous household servants to run their homes.

These Bungalows were constructed with a timber framework that was covered in reed rushes and earth. The entire structure was then plastered together with cow dung and then finally whitewashed.

There was always a wide veranda encircling the entire building.

Each bungalow was surrounded by its own corn field, flower-garden and neatly trimmed hedge.

The interiors were typically austere but featured spacious, airy rooms with high ceilings and whitewashed walls.

The rooms were usually situated on either side of a long hall which ran down the center of the house.

Wallpaper was pointless since white ants would have eaten it. The floors were made of beaten mud – termites love wood – and covered with bamboo or rush matting.

Beds were draped with mosquito nets. Thick mats woven from fragrant grasses called tatties hung in doorways and windows. In the hot season, a man servant would throw a bucket of water on these mats making the house cool and sweet smelling.

Most furniture was constructed of bamboo with cushions added for a little comfort.

Piped water was often available but electricity was rare. Before electricity arrived, lighting would have come from paraffin or coconut oil lamps.

Each bedroom had a bathroom but, before piped water, a hole was drilled into the floor through which the water from a tub or bowl would drain.

By the 1930s, though, there were flush lavatories and running water.

The only Indians found inside these compounds were the household servants whose quarters were situated at a distance from the home.

Without exception, European families employed an army of servants in India.

During the 19th century, these servants were the only group of Indians with whom memsahibs (British women) had substantial contact. Domestics were an indispensable part of everyday life for most British families in India.

Throughout the century, memsahibs arrived in India with preconceived assumptions about the number of domestics to employ, what to expect in the way of services from them and how to deal with them - all based on instructions from manuals intended for families living in Britain.

After their arrival, memsahibs were astonished to discover that British families in India, irrespective of their income, kept a large number of servants.

One woman recorded in her journal that they employed only the number of servants which were required - 19 in her case!

How did memsahibs justify employing so much domestic help? They claimed that the religious and social practices of the indigenous population forced them to hire numerous servants.

Because of their religious commitment, Muslim servants would not touch pork, often refused to serve wine and were unwilling to remove dirty dishes from the table or to wash them. According to the memsahibs, it was the Hindu caste system which multiplied the number of required servants.

In Britain, a housewife assumed that a servant’s normal duty began at 7:00 AM and ended around 10:00 PM. In India, the situation was different.

Each domestic job - which normally required just a couple of hours to complete - was specialized and only that particular person could perform it. And, following the completion of his task, the Servant would take a rest.

Typically, a family needed -

A khansama - the cook........ayahs for the children ..... a jemader who belonged to the lowest caste and came in daily to sweep and wash the floors and keep the bathrooms and toilets clean......

a mali who looked after the garden .......

A Syce who took care of the horses and chauffeured the family around .....

A durzi, an Indian dressmaker, who could recreate clothes from any picture given to him. He would arrive at the house equipped with needles and thread and his own Singer sewing machine.

In the evening, the bheesti came with his goat skin bag and went round the bungalow sprinkling water into the dust.

Since there was no air conditioning, a punkah wallah might be employed.

His job was to fan the sweltering family. A string or rope would be run through a window to a man who was outside on the veranda. This string was attached to a heavy length of cloth which was suspended on a beam across the ceiling. To cool the room, (often while lying on his back) he’d pull the string - which was sometimes attached to his big toe.

But the main problem for the memsahibs was not merely the number of servants to be supervised. It was their physical darkness.

The servants they employed came primarily from the dark skinned indigenous population. For many, this direct contact with a dark skinned person occurred for the first time with their arrival to India since very few British women had direct contact with dark skinned people at home.

The experience of hiring and supervising these domestics was unsettling to many of the British women.

Most memsahibs could not speak nor understand Hindu, nor any Indian language, so they often miscommunicated or misunderstood their servants.

These linguistic barriers contributed to the intolerance of memsahibs to the habits of the indigenous domestics. Their perceived image of the servants was that they were lacking in intelligence.

Memsahibs were the most travelled members of the family since, if family finances allowed, they were constantly migrating between Britain and India.

While sailing, affluent seasoned travellers avoided the worst of the sun onboard ship by travelling “port outward and starboard home” – hence the arrival into the English language of another Indian based word, POSH.

In analyzing the cultural roles of women during the British Raj, historians assert that socializing amongst themselves became one of the major duties of the wives of officers.

One of the first social functions for the newcomer to India was to drop her visiting card on British residents in the area. A small black box sat outside every front door, and anyone who was a newcomer or who wished to make contact, could drop in their visiting card giving details of who they were and why they had called.

The wives of British officers were expected to attend countless military and social functions. They were also frequently obligated to host formal and informal dinner parties and gatherings.

The account of one wife - Mrs Maud Diver - contains a long list of required social activities that included frequent balls, visiting, tennis, playing cards, watching polo games and croquet.

Colonels’ wives, she recorded, were expected to “dine the station” regularly....... while the Captains’ and subalterns’ wives found themselves equally duty-bound to provide parties “for the honour of the Regiment.”

Such was the life led by Edwin and his wife, Enid, during their years in the Bengal of India.

In 1899, Edwin was shipped from India to South Africa to serve during the Second Boer War. His wife and daughter returned to Southampton but Enid was able to visit her husband in Africa on several occasions.

Edwin returned home from the War in July 1902 and the family was reunited in Southampton where they lived at Ardmore House on Darwin-Road.

In August, 1905, twelve year old Gladys competed at water polo at the Nautilus Swimming Club.

Three years later, her father was committed by his brother George to a psychiatric hospital where he died on October 1, 1907. His body was never claimed by the family so he is buried in an unmarked grave near the Asylum.

Enid next appears in the 1911 Census. She is a patient living “on her own means” at the Dorset Lunatic Asylum.

She seems to have been committed to this public institution since, at least, 1908 when all of her household furnishings were sold at public auction.

Her husband had died in October 1907 and the auction was held exactly a year later. On November 8, 1908, Gladys and her uncle were on a ship heading to Ceylon - exactly one month after the auction.

A very sad story, indeed.

Born in 1859, King Hermann Plumridge was Enid’s older brother. We can assume that, knowing the family circumstances, he had invited Gladys to come to Ceylon where he had been living since around 1883. His brother, Preston (1853-1919) was also a Tea Planter living in Ceylon.

K H had retired his commission as a Lieutenant in the Norfolk Militia in 1878 when he was 24.

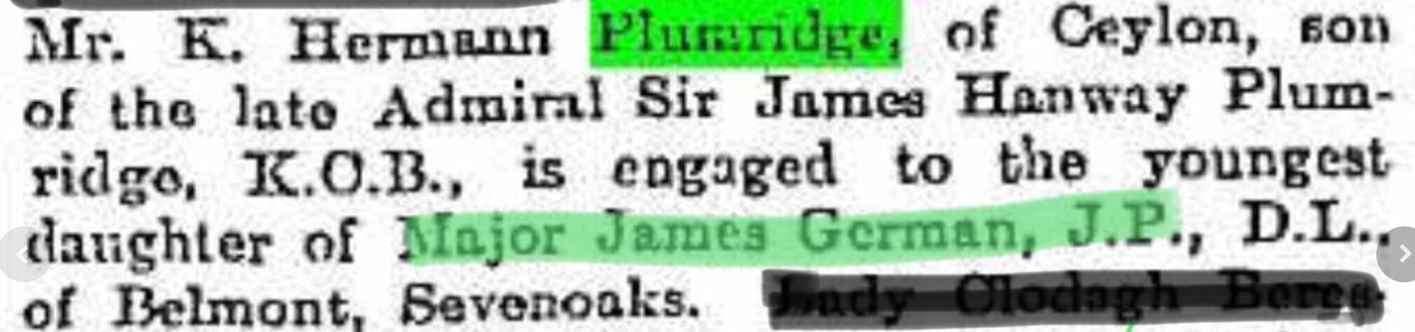

In 1901, his engagement to his cousin -the daughter of Major James Fisher German, (barrister-at-law and Justice of the Peace for Kent and Lancaster) - was announced.

Her name was Ethel German.

Ethel German was born in 1874 at Belmont House in Sevenoaks, Kent.

Unfortunately, the wedding never took place. No details are known. Ethel left the country soon afterwards. She died in North Carolina a few years later in 1907.

She is buried in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina.

King Hermann left England, too - returning to Ceylon with Gladys.

From 1883 until 1928, he had managed or owned a total of 20 Tea plantations there and died in Ceylon in 1929. He is buried in the Anglican Cemetery in Colombo.

Our Plumridge family has a long history in Ceylon.

In 1833, Lieutenant-Colonel George Burrell was in command of the 18th Royal Irish Regiment in Ceylon.

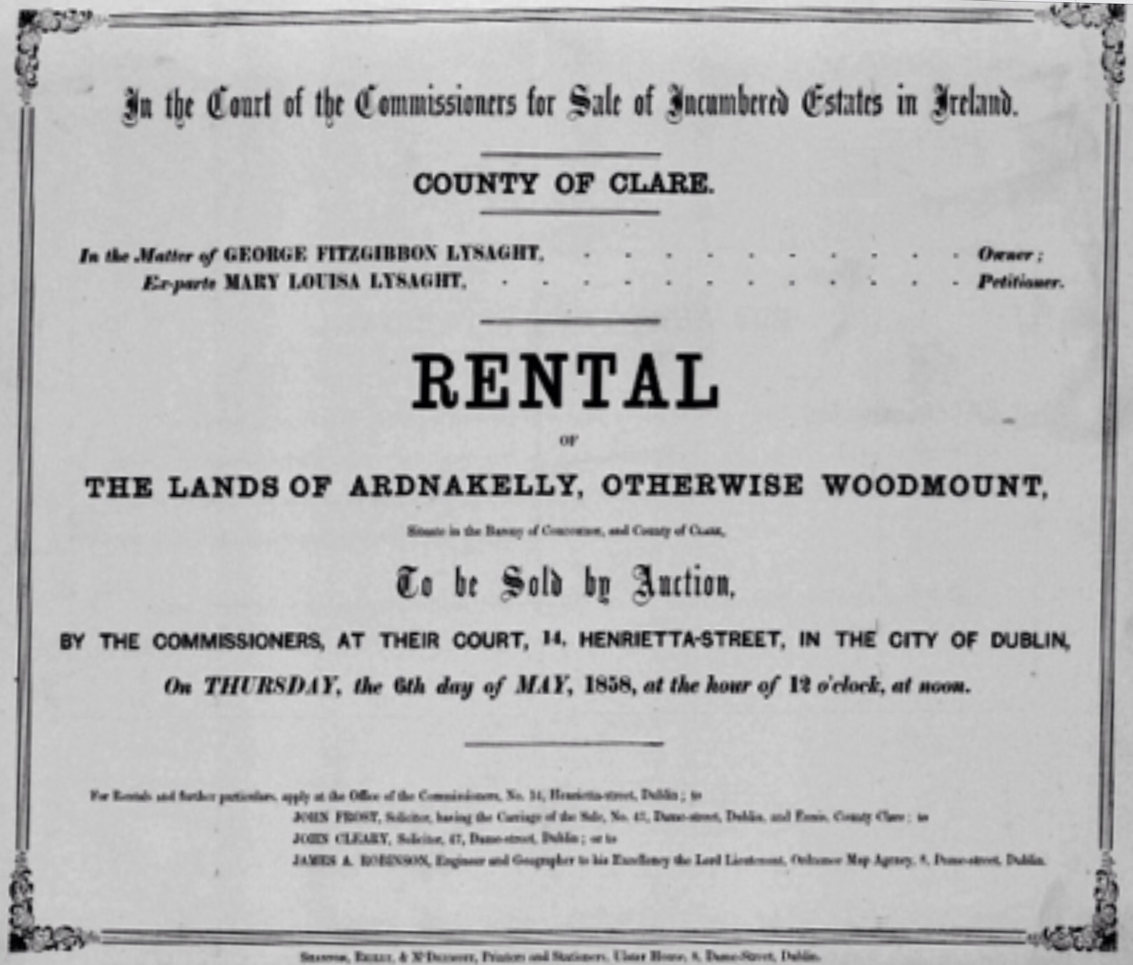

His daughter, Georgina Burrell (1818-1866) married the “Road Maker of Ceylon” - Col Thomas Skinner (1804-1877) - at St Paul’s Church in Pettah, Ceylon on December 19, 1838.

Major Thomas Skinner had a sister who was named Georgiana Skinner.

Georgiana Skinner married the twice-widowed Admiral James Hanway Plumridge at St Stephen’s Church in Trincomalee, Ceylon on August 28, 1849. She was 27 and he was 62.

King Hermann and his sister, Enid, were two of their children.

Georgina Burrell Skinner died on the Red Sea on August 19, 1866. She was only 44 years old and left seven children. Although her body was buried in England, her heartbroken husband commissioned a Memorial to her at Christ Church in Galle Face, Ceylon.

“Sacred to the memory of Georgina, the beloved and honored wife of Major T Skinner,

Commissioner of Public Works, Ceylon, daughter of the late LT-General Burrell, C.B.

Born 20th June 1818, died in the Red Sea (Lat. 25-04N Long. 35-16E) 14 August 1866.

A true and devoted wife, an exemplary mother, a sincere friend,

she lived in spotless honor and consistent truthfulness of character,

strong in the faith of her Saviour’s love and in the efficacy of His atonement.

She lived in the assured hope of a resurrection to eternal life

through the sacrifice and the righteousness of the Blessed Redeemer.

That her seven children may honor her memory in striving by God’s help

to follow her precepts and to emulate her example,

that her love of truth in thought, word and action and

her uncompromising and enduring virtues may shed an illumination

on her descendants to come and that England may long be blessed with such mothers for her sons is

the earnest prayer of her bereaved husband.”

Major Thomas Skinner had arrived in Ceylon in 1818 - when he was only 14 years of age.

At that time, the journey from Colombo to Kandy - across swamps, jungles and ravines - took about six weeks.

Two years after his arrival, young Skinner was entrusted with the construction of a most difficult section of the road to Kandy.

His extraordinary efforts brought this almost inaccessible region of Ceylon within a 5 days’ march of Colombo. The success of that enterprise was mainly due to the genius of that young man.

Becoming an officer of the Ceylon Rifles, he had applied military organization to enlist a workforce of 4,000 trained indigenous laborers. With this “army”, he spent 50 years in the construction of roads and bridges throughout the Island - often undergoing the greatest privations during his surveys of the trackless wilderness.

Major Thomas Skinner is known as the “great road maker of Ceylon”. He left an account of his work in his autobiography published in1891: Fifty Years in Ceylon.

The network of roads that now exist all over Ceylon is his lasting memory.

Upon his arrival in 1818, there were no roads. At his departure, there were 3,000 miles of roadways - mostly due to his genius, pluck, energy and self-reliance.

When he left the Island in 1867, his 50 years of incessant work were thus summarized in the Ceylon Observer:

“..... He has survived to see a magnificent network of roads spread over the country, from sea-level to the passes of our highest mountain ranges; and instead of dangerous fords and ravines where property often suffered,

he has lived to see every principal stream in Ceylon substantially bridged or about to be spanned by structures of stone or iron.

Whereas, before his time, there were strictly no roads in the Island.

Ceylon, with an area of 25,000 miles, can now count nearly 3,000 miles of man-made-roads,

one-fifth of which consist of first class metal roads.

Add to that the restoration of inland navigation - the canal system- and the impetus given to many another public work and we have the bare outline of such a life of unselfish usefulness to his fellow-men as few have been privileged to show...”

With such a background in his family history, it is no wonder that K. H. felt comfortable making a life for himself in Ceylon. And, Gladys probably felt comfortable with her extended Ceylonese family, too.

The 19th century marked the emergence and consolidation of the ‘Tea Planter Raj’ in the interior hill country of the Island - Kandy.

In Colombo, there were palm trees, brilliant yellow cassias, scarlet flamboyants, and a whole host of other flowering trees everywhere. The walls and sidewalks were clothed in bouganvilleas of every color and ginger lilies of every description thrived in the hot, sticky clammy heat.

Almost every day, there were sharp thunderstorms which drenched the land with rain but were followed in turn by brilliant sunshine, so that the hothouse environment completely dominated ones life out there.

However, from its elevation, Kandy enjoyed a year-round climate rarely experienced in Europe.

The annual temperature averages 76* but seldom reaches over 72*. This, in addition to its many other advantages, renders Kandy the most agreeable spot to live in all of Ceylon.

In 1908, the train trip upcountry from Colombo traveled through the steamy low country of palms and rubber trees, into the great open vistas of the tea country.

The single track railway itself was a marvel of engineering - hacking its way through precipitous granite mountains, with a sheer determination of tunnels, terraces, bridges which had all been blasted out by hand with gunpowder and dynamite.

Eventually, some eight hours after leaving Colombo, the main line train stopped at Nanoya station. From there, passengers transferred to a minor narrow gauge for the remainder of the trip to the hill station of Nuwara Eliya which was 6,500 ft above sea level and cool.

In 1840, coffee plantations were exploding all over Kandy.

But, in the 1870s, the coffee industry could not survive the devastating effects of a fungal disease called Hemileia vastatrix or coffee rust, better known as "coffee leaf disease" or "coffee blight” which ravaged the crop in the central mountains and southern foothills.

Coffee estate owners left in droves, selling their land at rock bottom prices to the newly arrived tea planters.

By the late 1880s, almost all the coffee plantations in Ceylon had been converted to tea.

The high altitude and lush green terrain of Kandy’s mountainous region with its waterfalls, streams and cool pure air offered ideal conditions for the production of tea.

Once occupied by deep jungle - home to elephants, leopards and a variety of fauna and flora - the area had been stripped bare by early coffee growers to make way for the planting of crops, roads and a railway. For this very reason, the transition to tea planting was practically seamless with thousands of Indian Tamil immigrants previously employed on coffee estates now turning their efforts to tea.

The tea planter was afforded almost complete authority and impunity within the plantation, and enjoyed enormous influence on labor, economic and social policy throughout the Island.

Samudra Ratwatte, a Sri Lankan tea planter’s wife, described plantation life as an idyllic and traditional existence.

It was a fiercely English way of life that played out on estates dotted with quaint stone residences, clubhouses and golf courses that had been established in the 19th century.

Domestic staff prepared typically British menus and socializing involved tea and dinner parties at which the senior planters and their wives played games and sang old English ditties.

The plantation was a ‘total institution’.

For its laboring population, the Plantation was home, community, and workplace.

It was where almost every aspect of the life of the worker – from ‘womb to tomb’ as the Planters’ Association repeats to this day – is situated within its boundaries. These aspects include education, health care, spiritual needs and recreation.

By design it was, and to a great extent remains, distanced – spatially, administratively, and legally – from the rural social formation in which it is implanted.

But, for the planter and his family, plantation life was living like the royals did...... and in certain ways, sometimes better.

It was into this plantation life that Gladys Muriel Milward entered when she landed in Ceylon in 1908.

King Hermann had prepared the way. He had arrived in Ceylon in the early 1880s.

According to Sir Thomas Villiers, in his book on the tea industry, Ceylon was clearly an attractive place for young men at this time.

‘[O]ffice life or industrial life did not appeal to every one, many of them looking for an open air life.

Agricultural life in England was on the decline.

The usual openings in the Navy and Army were very keenly competed for […].

Ceylon seemed to many of them to offer just the life they wanted’ .

It is easy to understand this way of thinking and how it might be applied to KH.

Records show that he had been the manager of over 20 different tea plantations in Ceylon from 1883 until 1927.

By the time Gladys arrived in 1908, he had managed Sherwood, Warleigh, Lynsted and Angroowelle Plantations.

He was also a member of several clubs and organizations in Ceylon.

These include: the Bogawantalawa Planters Club, the Ceylon Poultry Club (which introduced pure young chickens to Ceylon), the Ceylon Nursing Association, the Knights Templar and a total of three Freemason Lodges (St George Lodge, the Adams Peak Lodge, the Nuwara Eliya Lodge and the Kurunegala Lodge).

(Incidently, the early Knights Templar had attempted to unite the world's religions after returning to Europe from the Holy Land during the 12th-14th centuries. They amalagamated the rites they had learned in the Middle East with those they had adopted through their Roman Catholic upbringing. The knights were eventually tortured and burned at the stake for heresy but their goal of a universal spiritual tradition survived and was later taken up by small bands of knights and secret societies spawned by the Knights Templar, including the Freemasons and Rosicrucians. The Knights also agree with the Islamic tradition of situating the Garden of Eden in Sri Lanka.)

King Hermann was also a Trooper in the Ceylon Mounted Rifles - the first Mounted British Corps in the Island - which was introduced in 1897.

By the time Gladys had arrived in 1908, her Uncle was well established and well known in Ceylon.

So, it comes as no big surprise that a wedding announcement was soon published in the British newspapers. Gladys Muriel Milward and Walter Henry Brymer were to be married in 1912.

Walter Henry Brymer was also a tea planter and he and KH were members of many of the same clubs and associations in Ceylon.

Walter came from a very distinguished family.

In 1827, his maternal great grandfather, George Tugwell, had established the Tugwell, Brymer, Clutterbuck & Co Bank in Bath with his grandfather, John Brymer, and his great grandfather, Daniel Clutterbuck.

As you can imagine, the families were incredibly wealthy.

Walter’s father, Walter Spencer Brymer (1854-1926), was born on the most famous Street in the city of Bath ..... at 17 Royal Crescent.

Besides working at the family bank - he owned expensive property on the Pall Mall in London - he spent most of his time devoted to sport and charity events.

His obituary best narrates the life he led -

Here is another account of his life -

When Walter Spencer Brymer died in 1926, his funeral was attended by hundreds of people, including all the maids whom he had employed at his home at 13 Marlborough Buildings in Bath.

Noticeably absent from the funeral was his only living child, Walter Henry, who had been settled in Ceylon for quite a time. According to this newspaper article dated June 13, 1926, Walter had just been home on a long holiday from Ceylon before his father passed away. Perhaps he just could not take more time from his plantation.

So, sometime in 1912, Gladys Muriel Milward married Walter Henry Brymer.

A year later, on April 29, 1913, their first son, John Hanway Parr Brymer, was born in Maskeliya, Ceylon. John’s two middle names, Hanway and Parr, are names traditionally used by members on both sides of their families. Gladys’ maternal grandfather was Admiral James Hanway Plumridge and Walter’s great great grandfather, John Parr, was Governor of Nova Scotia in 1785.

In 1914, Walter was managing the Deeside Tea Plantation near Maskeliya. He was also a Trooper (with King Hermann) in the Ceylon Militia and Secretary of the Maskeliya Tennis Club.

The next year, on March 9, 1915, their second son, Hew Robin Guy, was born in Maskeliya.

Probably to meet the Brymer family in England, Gladys took her elder son to London in 1916. The two sailed on the SS City of York and landed in London on May 23.

Walter became manager of the Sheen Tea Plantation in 1920 and continued in that position for ten years. During this time, the family lived in the Manager’s Bungalow on the Plantation.

The Sheen Plantation in Pundaluoya was established in about 1870.

Imagine living in such a bungalow!

Here, in the alluring hill country of Sri Lanka, some of the finest tea in the world is still grown at an elevation exceeding 4,000 feet.

Tea is still grown at Sheen.

This will conclude Part One of the story of Edwin Oswald Milward’s descendants.

Please stay tuned for the next chapter.

Family Tree

Our Great Great Grandparents: Ellen Maria O’Brien and John Harnett Milward

Our Great Grandmother: Mary Frances Milward Reilly

Her brother, our 2nd Great Uncle and his wife: Edwin Oswald Milward, MD and Enid Susan Plumridge Milward

Their daughter, and our 1st Cousin, 2x Removed: Gladys Muriel Milward Brymer and her husband, Walter Henry Brymer

Their sons and our 2nd Cousins, 1x Removed: John Hanway Parr Brymer and Hew Robin Guy Brymer.

EPILOGUE

History gives a nation its bearing on what it is and how its people are affected by what has happened in the past.

Its kings and queens, its wars - with victories and defeats - these all mold a nation’s culture into the way it views itself in the present.

In the same way, a family history presents how a family has survived and come to terms with the great social and cultural experiences of the ages.

We hope these stories will give each member of our family a foundation and, in some small way, explain how we came to be what we are today.

Hopefully, through these vignettes, our future generations will gain a knowledge of the energy and dynamism, the loves and hates, the errors and mistakes, the victories and failures, the struggles and successes that make us what we are.

Our family history presents a fascinating read - and, hopefully, some lessons to be learned in the process.